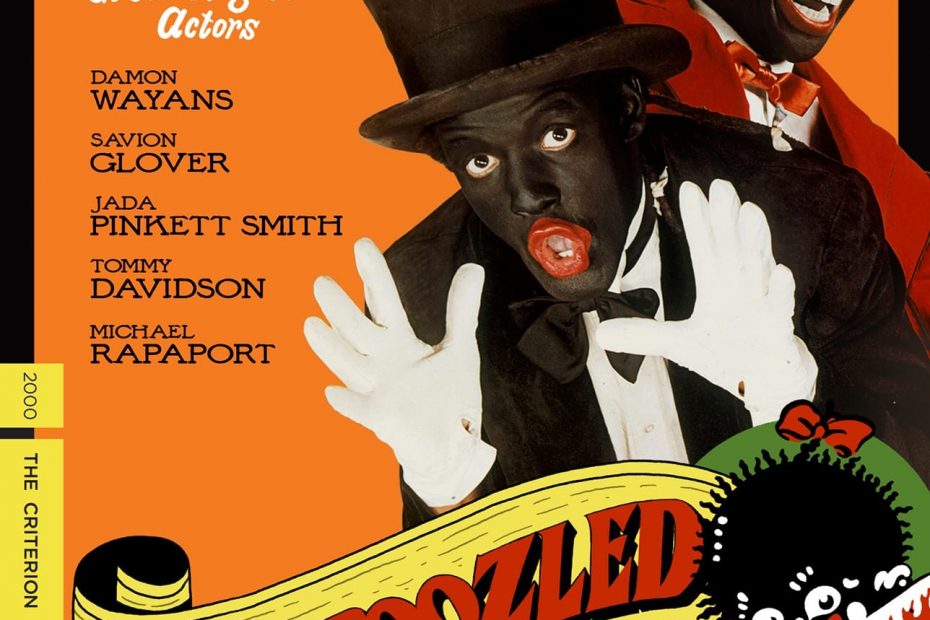

“BAMBOOZLED” by Spike Lee: A Movie Review written by Evan Jacobson for a college class: A survey of African American Literature, University of Washington, circa 2003

Spike Lee’s latest film “Bamboozled” is a satire exploring several themes. First, Thomas Dunwitty (played by Michael Rapaport), the White boss of the CNS television network, considers himself to be an authority and expert about Black culture. Second, Pierre Delacroix, the lead/narrator played by Damon Wayons, is a Black Harvard Graduate that identifies with Whites more than Blacks. Finally, several characters are bamboozled (denotatively defined–to deceive) at the beginning of the story and suffer tragic consequences at the end.

Delacroix is the only Black person and Harvard Graduate to write for CNS, a White network with poor ratings. The pressure is on Delacroix to save his job by writing a groundbreaking show that will please Dunwitty and boost television ratings. Delacroix decides to reinvent the wheel by developing a highly ridiculous, stereotypical, and satirical farce based upon “Black-face” minstrels from the past. This farce assumes the shape of a variety show featuring Manray (played by Savion Glover), a homeless tap dancer, and his humble and garrulous sidekick, Womack (played by Tommy Davidson). Both Manray and Womack agree to change their names to “Mantan” and “Sleep and Eat” as per their business contract. Later on, I will discuss the implied symbolism regarding their purposefully chosen names; the plot thickens…

Delacroix’s spoof is entitled “Mantan (sic) The New Millennium Minstrel Show,” and it turns out to be successful, much to his chagrin; the television ratings go through the roof. The show also inspires a cultural phenomenon: White people actually put on the Black face to actively accept, participate, and attend the live taping of the show. Despite the show’s well-received notoriety in the eyes of both viewers and media, however, it eventually becomes a detriment towards the cultural, social, political, and moral views towards people of color. Moreover, the show’s success is also the beginning of the end as the all of the movie’s characters question their own identities and ultimately, deconstruct their own views about mocking Black culture.

Delacroix’s character contains a duality commonly known as dramatic irony–knowledge possessed by the audience (or reader) that the character is unaware of. This is certainly the case as Delacroix perceives himself to be equal to that of a White person at CNS. In reality, however, he is an unequal, inferior puppet, and not in control of any decisions at the network. Hence, he is bamboozled by CNS because he is led to believe that his writing input really matters, which is ironic.

Thomas Dunwitty’s obvious White role is significant because he considers himself an expert in Black culture, and justifies his expertise because he is married to a Black woman, is the father of Black children, and obsessed with many famous Black figures, such as Mike Tyson, the Boxer, and Willie Mays–a Baseball legend. Hence, Dunwitty feels more connected to Black culture than Delacroix. At the beginning of the film, Dunwitty and Delacroix are having an important conversation about connecting with Black culture. According to Dunwitty, “you [Pierre] are not Black enough. In fact, I am more Black than you. . . I’ll give you a thousand bucks if you can name that Black guy on my wall. . . ” When Delacroix failed to name the particular Black figure, it showed the viewer that Delacroix is disconnected from Black culture.

Here are some other points to conclude about Dunwitty’s (sic) role. First, he holds a prestigious position of power at CNS, which depicts authority to feed his megalomania. He is also motivated to save the network by amassing the highest ratings, which, in turn, allows him to “take over Black culture,” according to Spike Lee. Finally, as a result of being an expert, it allows Dunwitty to exercise power and ultimately mock Black culture, which helps contribute to the tragic events at the end of the film.

Check out this trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aPBmOEpviOg

Years ago, in a college television media class, I learned that character names are specifically chosen, rather than being chosen arbitrarily. Dunwitty’s name, for example, might possibly satirize Black dialect and irony. When I lived in the south, for example, I heard many folks say “he’s done finished.” “Done” is used as a helping verb and “has” is not used (verbally speaking) despite its correctness. I can go further and suggest the following statement: “he’s done witty cause he’s so smart and knows what’s best for us Blacks.” This example, albeit far-fetched, could provide a sound rationale for using the name Dunwitty to depict a ratings-hungry-Black-wanna-be-expert archetype. Another example of specific name-choosing and satire is evident in the character of Sloan’s brother, a radical hip hop rapper with two names: “Big Black” and “Julius.” The character’s former name is used often, especially when he hangs out with his rap group, “The Mow Mows.” The latter, the character’s birth-given name, is considered a slave name. Ironically, the character does not like to be referred to as “Julius.” This is important to mention because an underlying duality suggests that “Big Black” is very happily connected to his Hip Hop, Gangsta (sic) lifestyle, but uneducated and considerably disconnected (by choice) from Black history–even slavery. Finally, “Mantan” is specifically chosen to depict and highly satirize the role of Black face, which is totally ironic in itself, i.e. the Black man with a tan. Moreover, Black men are not Black enough so they must paint their faces with a paste comprised of burnt cork, as to make their blackness even more obtrusive.

Mocking Black culture is a recurring theme throughout the film. In addition to wearing Black face (mentioned earlier), the minstrel show reiterates the following ironic and self-deprecating mantra: “Niggaz (sic) is a beautiful thing.” The pejorative term “Nigger” is also used in an advertising context; Tommy Hilfiger, a popular style of clothing, is renamed “Timmy Hilnigger (sic).” This is another attempt to satirize wardrobes commonly worn amongst Blacks, arguably. One final example of mocking Black culture is also apparent when CNS hires a public relations expert on African American History–a contingency plan just in case something goes awry with the show. Moreover, this expert, a Jewish woman, claims to use Martin Luther King Junior’s name as a rhetorical strategy to save face for CNS. If that fails, she can inform the press that the minstrel show and its infrastructure are (a legitimate) part of the Black community and serving the public interest. Hence, the role of this public relations person, albeit small, provides the viewer with another symbolic (and ironic) example of a White expert purporting to be an expert regarding Black culture.

Ultimately, being bamboozled or deceived results in tragedy at the end of the film. First, Mantan (sic) ultimately refuses to wear Black face and quits the show. Then, he is taken hostage by the Gangsta (sic) rap gang, “The Mow Mows,” and forced to tap dance on live television before he is brutally shot and killed. Second, all of The Mow Mows are gunned down by the police, except for the one White guy in the gang (named MC SEARCH) who is merely arrested for murder. In fact, MC SEARCH kept yelling emphatically, “why didn’t you shoot me?” This rhetorical question exemplifies ultimate deception because the White police killed all of the dangerous Blacks, but MC SEARCH was still standing immediately following the melee. Finally, Sloan is bamboozled by Julius’s surprising death, and reacts by both blaming and shooting Delacroix.

In conclusion, I enjoyed the satirical irony contained within this film because it raises many questions about perceptions of Black culture. Moreover, it represents an inexplicable bandwagon for White people, i.e. wanting to become Black, identify, and assimilate into Black culture; the Whites also yearn to connect with contemporary artists who also identify and consider themselves hip, Black musicians (e.g. Vanilla Ice, EMINEM, et al.). Also, “Bamboozled” has opened my mind to reevaluating Spike Lee movies and other movies regarding Black culture, media influence, and various cultural and ethnic perceptions. Finally, I also had an opportunity to explore Black face and Minstrels, a topic for which I was unaware of prior to viewing the film.

Review written by Evan M. Jacobson, ©2003

No part of this review is to be printed without permission by Evan M. Jacobson, ©2003